Lost history excavated from Adirondack soil

A quest by a SUNY Potsdam archaeology professor to uncover the roots of abolitionism in the Adirondacks and her search for a lost African American settlement built to fight slavery and social injustice are woven through a documentary by New York filmmaker Paul Miller.

Aerial photo of John Brown Farm State Historic Site in North Elba, N.Y. (Photo by Paul A. Miller)

The narrative thread of Miller’s film, “Searching for Timbuctoo,” begins in 1846, when wealthy landowner and abolitionist Gerrit Smith gave away 120,000 acres of land in Essex and Franklin counties to more than 3,000 African American families—a measure that afforded the families an opportunity to farm and served as a direct rebuke to a racist New York State law that limited voting rights to Black males who owned land valued at a minimum of $250. Called “Timbuctoo,” one of these experiments in social justice out of multiple settlements drew such reformers as Fredrick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and John Brown in the gathering tensions leading up the Civil War.

To bring the narrative thread into current times, Dr. Hadley Kruczek-Aaron, chair of the SUNY Potsdam Department of Anthropology, worked through five seasons and multiple digs to unearth fragments of the story from the soil of the settlement near North Elba. Intent on documenting whatever history he could find, Miller followed Kruczek-Aaron and her field school as they searched for artifacts at the John Brown Farm. Brown and his family moved to the land in 1849 to mentor the farmers, and he was buried there after his execution in 1859.

“I wanted to follow Hadley's work as a metaphor for uncovering these forgotten histories,” said Miller, a graduate of the University at Albany with a 20-year career in broadcasting and cable television.

The film unwinds the histories of influential abolitionist figures, uncovers all-but-forgotten actors in the turmoil of the pre-Civil War years, weaves their stories with Kruczek-Aaron’s detective trail and finally leaves room for the many remaining mysteries of Timbuctoo. Featuring narration by Albany civil rights activist Dr. Alice Green and New York Congressman Paul Tonko, the film drew crowds at its screenings in central and northern New York, nourished community discussions and was featured on public television channels while inspiring an exhibit at the New York State Museum in Albany.

“I'm very gratified that more and more people find the film worthy of their time,” Miller reflected. “My goal was to do justice to the story so that others would be equally impacted and realize that there are unknown histories all around us.”

Paul Miller filming in the Adirondacks (Photo by Paul A. Miller)

The remembered—and forgotten

The exploits of John Brown—his vision, violent hatred of slavery, and raid of the Harper’s Ferry arsenal that catapulted the nation into armed conflict—are the stuff of history books. By contrast, much of the detail of Timbuctoo’s brief but promising time and the saga of these early Black settlers have been buried. The fate of those most impacted by slavery and the land grants—the Blacks who made the journey from as far away as New York City to break the sod and try their hand against the harshness of the North Country—has left faint imprint on the land and the annals of local history, with few exceptions.

Keen to fill these gaps where possible, Kruczek-Aaron was particularly focused on increasing knowledge of the experience of these farmers, as well as the lesser-known activists who helped them. This included Brown’s wife Mary, whose everyday acts of support were key to history and yet overlooked.

“Archaeology helps us to answer questions like: What were they eating and drinking? Were they taking medicines? Were they canning produce? How were they setting up their farms? Were they repairing, recycling, or reusing items?” Kruczek-Aaron explained. “My focus is not on whether these farmers found success or failure, which is what early historians have tended to dwell on—often in racist terms—but on how the grantees and those who supported them responded to the challenge of living in the Adirondack woods as part of this history-making reform experiment.”

"I can say without hesitation that it has been the most meaningful research of my career.”

Michael Madeiros ’19 looks on as Dr. Hadley Kruczek-Aaron inspects a bottle found on abolitionist John Brown’s farm in Lake Placid, NY, as part of SUNY Potsdam’s archaeology field school in 2017. (photo by Jason Hunter)

Especially since the Brown family was the backbone of the farm while Brown himself was away fighting against the slavery system, Kruczek-Aaron sought to understand how wives and daughters used Smith’s land grants and furthered the abolitionist cause at an organic level. She and Miller also focused on Lyman Epps, an African American settler who was a close friend of John Brown and whose family would go on to endure in the Adirondacks for generations. Epps was a well-known music teacher, assisted in establishing the Lake Placid Library and helped to break a trail to Indian Pass, among other contributions to regional history.

Vapors and molder

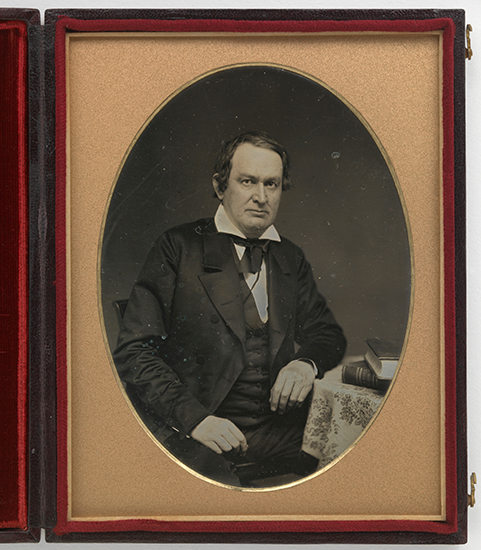

The quest to do any real justice to Timbuctoo has been frustrating, tantalizing, and hard to give up. The lack of clues points to a flaw in the history-making process itself—the capricious way that important stories are ignored or lost, while others are carried forward and form the foundation of our understanding, however incomplete. These vagaries affect not only the marginalized, but even those with wealth, influence and memorable narratives. Haunted with fear of prosecution for his financial support for Brown’s work and by the stress of a nation coming to a boil, Smith suffered a mental breakdown, was committed to an insane asylum and recovered. Yet through the filming, Miller was amazed by the way even Smith eventually vanished into obscurity.

“What is striking to me is how stories and even prominent people are easily forgotten,” Miller said. “In the mid-19th century, Gerrit Smith was one of the most well-known and powerful abolitionists in the country. You see his name in the headlines of newspapers of the time. He was nominated for president of the United States and governor of New York multiple times. He was elected and served in Congress. He was one of the wealthiest and largest landholders in New York. But today, hardly anyone knows his name or what he did.”

“What is striking to me is how stories and even prominent people are easily forgotten,” Miller said. “In the mid-19th century, Gerrit Smith was one of the most well-known and powerful abolitionists in the country. You see his name in the headlines of newspapers of the time. He was nominated for president of the United States and governor of New York multiple times. He was elected and served in Congress. He was one of the wealthiest and largest landholders in New York. But today, hardly anyone knows his name or what he did.”

Thanks to Miller’s film and to Kruczek-Aaron’s toil, a light has been brought to a pivotal moment in the Adirondacks’—and the nation’s—history. Miller considers himself a storyteller rather than a subject matter expert, so he doesn’t expect to devote a great deal of further time to unraveling Timbuctoo. Instead, he’ll leave it to archaeologists like Kruczek-Aaron, future SUNY Potsdam students and local historians like Amy Godine to keep up the detective work.

“I’m eternally grateful to Hadley and her students for allowing me to follow them for four weeks while they did the hard work of, literally, moving earth,” Miller said. “It was fascinating to watch their painstaking process and it gave me an appreciation for how challenging the task of unearthing artifacts really is. But there's also a very real thrill when they pull objects, whether pottery fragments, bullet casings, or remnants of a tobacco pipe.

“It forces you to imagine the last time those objects saw the sunlight—100 or more years ago—and to try to visualize the people who last touched them and understand more fully what their lives were like. To me that’s a form of ‘living history.’”

“The most meaningful research” of a career

The search for Timbuctoo will go on, possibly for many more years. So far, the digs have revealed artifacts associated with other local families who supported the experiment, but not of the grantees themselves. However, Kruczek-Aaron is excited to have recently received permission to excavate sites on land owned by the Uihlein Foundation in Lake Placid, including the second home of Lyman Epps and multiple historic farms connected to Timbuctoo.

John Brown Farm State Historic Site in North Elba, NY. Lake Placid Olympic Ski Jump tower in the background. (Photo by Paul A. Miller)

“A lot has changed on that landscape since the Eppses left it at the turn of the century, but our goal over the next few field seasons will be to see if anything is still there to help us understand their Adirondack story,” Kruczek-Aaron said. “If we aren’t successful there, in the future—with the help of grant funding—I hope to use LIDAR, a remote sensing tool that can reveal subtle changes in the topography of a wooded landscape, to find additional clues to the locations of the original farms established by the grantees.”

Although the archaeological search has not been as fruitful as she would have liked, and incredibly frustrating, the work has been successful in helping to put a spotlight on the Timbuctoo settlers and, to borrow a phrase from Gerrit Smith, on the broader “scheme of justice and benevolence” that they helped to realize, she said.

“Their story is one of courage, family, community, survival, and resistance in the wake of injustice,” Kruczek-Aaron said. “It reminds us of the gaps that exist in the narratives written about our nation’s history; it teaches us about the ways that certain historical narratives serve the interests of the powerful, and it helps inspire and inform efforts to fight for justice in the present and future.

“Given all of this, I can say without hesitation that it has been the most meaningful research of my career.”

Article by Bret Yager